The Penthouse

.jpg)

Director: Peter Collinson

Writers: Peter Collinson (writer), Scott Forbes (play)

Cast: Suzy Kendall, Terence Morgan, Tony Beckley, Norman Rodway, Martine Beswick

IMDB

Michael Haneke’s remake of his 1997 film Funny Games upped the ante in the current fad of “torture-porn” thrillers a la Hostel and Saw by making the victims much more personable and sympathetic than the usual beautiful but vacuous under-25 protagonists of these genre-of-the-moment exercises. As a result, our identification with them is turned against us when Haneke makes the audience voyeurs and accomplices in the victims’ ritualistic humiliation, torture and death. But that’s clearly his point – he wants to rub our faces in the violence that contemporary audiences seem to crave in so-called entertainments like Saw. If you don’t walk out on the film, then you deserve what you get. I don’t need to be subjected to Haneke’s litmus test to get the point (I already saw his 1997 original version) but what he’s doing isn’t original. Harold Pinter already explored this terrain much more artfully and effectively in some of his earliest plays. Take, for example, Pinter’s The Birthday Party (1957), which was adapted for the screen in 1968 and directed by William Friedkin: two mysterious men arrive unannounced at a shabby seaside boarding house and proceed to interrogate and torment a lodger there (who doesn’t appear to know them) until they drive him to the breaking point. Disturbing and darkly humorous, the violence in Pinter’s play is purely psychological and rarely physical.

Much more entertaining is the trashy but compelling Peter Collinson thriller, The Penthouse (1967), based on Scott Forbes’s play “The Meter Man.” It is clearly imitative of Pinter’s 1957 play yet Haneke’s Funny Games bares more than a passing resemblance to it. Is it a mere coincidence? Arriving toward the end of that period when films about “swinging London” were the latest craze – Morgan, Alfie, Georgy Girl, Blow-Up – The Penthouse could be viewed as a moralistic backlash against those movies and some of the hedonistic hipsters who populate them. Within the first five minutes of the film, the central couple, Barbara and Bruce, are established as illicit lovers. Barbara, who is your basic working class shopgirl, is clearly frustrated by their sporadic secret trysts and Bruce, a married real estate agent, is equally wary of the “when-will-you-ask-your-wife-for-a-divorce” discussions which inevitably follow their couplings. But there is already tension in the air, established under the opening credits of The Penthouse, as two sinister looking men gaze upward at the top of a sterile new high rise, see the lights come on in the penthouse, and then with a knowing smile between them advance toward the building.

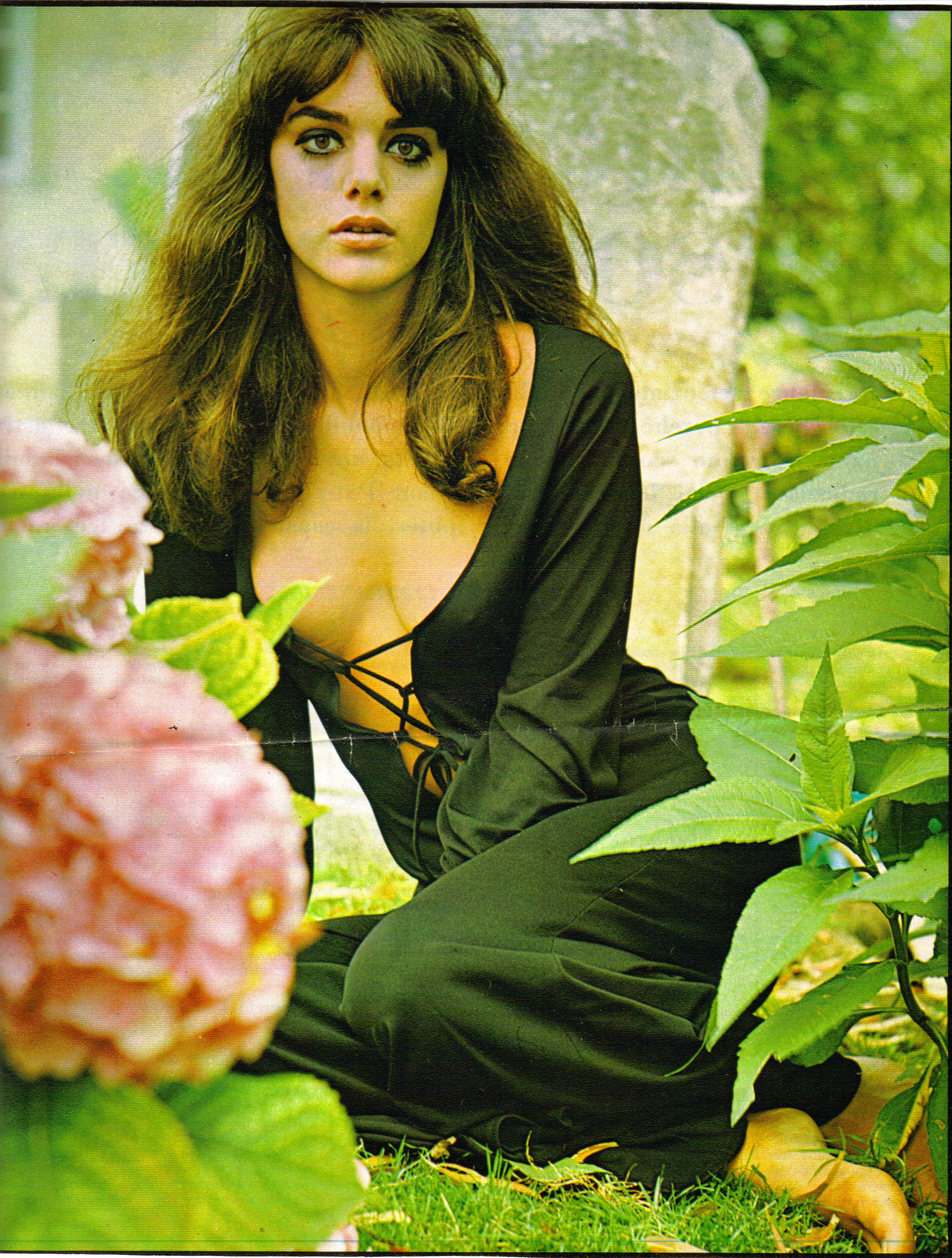

The penthouse in question turns out to belong to one of Bruce’s clients who is on vacation in the Bahamas and Bruce is using it without their knowledge. So, right from the beginning, we know Bruce is a jerk. He’s unfaithful to his wife, takes advantage of his mistress and his clients and is a spineless jellyfish to boot; we know this as soon as he sends Barbara off to answer the door when an unexpected visitor comes knocking, afraid their love nest will be exposed. As soon as she opens the door, the film crosses over into theatre-of-the-absurd territory as first Tom, and then his partner Dick, invade the penthouse, posing as meter men who have come to take the gas reading. They end up taking more much in both physical and psychological terms, and as their mind games become increasingly sinister, the film develops a compelling theatrical tension between how far Tom and Dick will go and how much abuse Barbara and Bruce will take before they fight back or snap. While Barbara is easily the more sympathic member of the couple (mainly because she’s played by the dazzlingly beautiful and sexy former model Suzy Kendall), neither character allows for easy identification because of the film’s highly stylized structure which emphasizes its stage origins. It allows us to experience the couple’s night of torment as a surreal, avant-garde happening – not hard-edged realism. Like other plays such as Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? where souls are stripped bare and relationships built on hypocrisy crumble when forced to face the truth, this one ends with Bruce and Barbara forever changed and damaged by their ordeal, unable to face each other again. It’s as if Tom, Dick and Harry (more on “him” in a minute) were externalized versions of each other’s worst fears come home to roost.

But back to The Penthouse. The type of funny games Tom and Dick favour seem to have no rhyme or reason other then breaking down their victim’s will. When they first gain entrance to the penthouse, they start by berating Barbara, who presents herself as the actual tenant, for not knowing where the gas meter is. Bruce, who pretends to be sleeping while overhearing Barbara’s harassment, finally rouses himself for a confrontation, only to be threatened with a switchblade. Tom and Dick then bind Bruce to a chair with silk cords, spinning him around until he is completely ensnared and forced to watch while the duo force Barbara to get drunk and strip down to her underwear. And so it goes, one humiliation follows another and Bruce’s attempt to turn Dick against Tom by planting a seed of distrust between them leads nowhere. Finally the two intruders pack up their things and leave Barbara, who’s been ravished by them both, and Bruce to sort the whole thing out. But just when you think the whole ordeal is over, the games begin anew with the introduction of “Harry,” who claims she is Tom and Dick’s parole officer. Verifying that she has the two men in custody and in handcuffs in her police car, she appeals to Barbara and Bruce to see the duo one last time so that they can apologize and ask for their forgiveness. By this point in this movie, you know that Bruce and Barbara are condemned to repeat the same mistakes over and over again and so The Penthouse comes to a close with one more round of madness.

While The Penthouse is often self-consciously arty AND unapologetically exploitive – Barbara’s transformation into a docile sex toy is helped along by John Hawksworth “blue movie” music cues– it is also compulsively watchable with a powerhouse cameo by Hammer Films sex siren Martine Beswick (Slave Girls, One Million Years B.C.) as Harry (she receives third billing but doesn’t appear until the final fifteen minutes). Her perverse presence – she arrives in male drag and soon “lets down her hair” with a wicked laugh – is as much fun as Amanda Donohoe’s camp turn in Ken Russell’s The Lair of the White Worm (1988). In addition, the movie has some striking Pinter-like dialogue. When Bruce blurts out, “Why’d you have to do this? We haven’t done you any harm.” Tom responds, “Well, it’s not a question of that. It’s more a question of the harm you might do us.” Haneke’s dialogue in Funny Games follows the same ying-yang logic.

Tom and Dick may be absurd creations but their enigmatic relationship remains one of The Penthouse’s most intriguing aspects. While they both have their way with Barbara, their flamboyant behavior and bitchy banter between themselves wouldn’t be out of place in The Boys in the Band. At odd moments in the narrative, Bruce and Barbara’s degradation becomes secondary to Tom and Dick’s passive-aggressive role playing. There is one scene where Dick is having fun trying on Bruce’s clothes as his victims watch and Tom sarcastically comments, “Dick’s rich you see. He’s terribly rich. You should see all the clothes he’s got. I don’t know where he keeps them all.” Disgusted, Dick strips off the jacket and throws it at Tom, saying, “I think this coat will fit you better than me.” Tom then flashes him an intimate look and says, “Maybe I’ll try it on a bit later” which brings a sly grin to Dick’s face. But the game remains a secret despite occasional signs that a clue will be revealed. It’s pointless to fight a tight, airless contraption like this but there is a certain fascination in monitoring your own reaction to it. What would you do if you were in Bruce or Barbara’s situation?

Tom Beckley, the actor who plays Tom, might look familiar to you. That’s because he played the twisted psychopath who terrorized Carol Kane in When a Stranger Calls (1979), his final film before he died of cancer in 1980. He was also appropriately creepy in Robert Hartford-Davis’s The Fiend (aka Beware My Brethren, 1972) and offered memorable support in Get Carter (1971). Norman Rodway as Dick is less familiar to American audiences since he spent most of his career working in British television but you can see him in Orson Welles’s Chimes at Midnight (1965) and Michael Winner’s I’ll Never Forget What’s ‘isname (1967), which also starred Welles. Terence Morgan, in the role of Bruce, is also an actor who received little exposure stateside but appeared in numerous British B-movie melodramas such as The Shakedown (1959) and Tread Softly Stranger (1958) and a few A-list titles such as Alexander MacKendrick’s Mandy (1952).

Those of you who enjoy Italian giallos or swinging sixties cinema from England need no introduction to Suzy Kendall, who first made favorable impressions in the James Bond imitation The Liquidator (1965) and To Sir, With Love (1967). Her film career has been eclectic, to say the least, and she’s appeared in a variety of genre films from the international espionage thriller Fraulein Doktor (1969) to the horror anthology Tales that Witness Madness (1973) to nunsploitation Diary of a Cloistered Nun (1973). However, it is her appearances in giallos that have earned her an international cult following for Dario Argento’s The Bird With the Crystal Plummage (1970), Sergio Martino’s Torso (1973) and his subsequent Spasmo (1974).

As for Peter Collinson, The Penthouse was his first feature film and he followed it up with Up the Junction (1968), also starring Suzy Kendall, in a working class expose that was firmly in the “Kitchen sink” school of British realism. His next film, The Long Day’s Dying (1969), a grim anti-war drama, received critical acclaim and won two awards at the San Sebastian Film Festival, but most of Collinson’s later work was ignored by the cinema intelligentsia though he is probably best known for The Italian Job (1969) starring Michael Caine. He died of cancer at the age of 44 the same year that Beckley died of the same disease.

The Penthouse is a film with a desaturated color scheme and the dominant color is gray – the skies are gray (one of the few exterior shots shows an urban landscape dwarfed by an industrial complex where toxic clouds of smoke are billowing forth from its towers) and the interiors are gray with some black and white highlights. Here and there are shades of sickly green on the walls or on furniture. And Arthur Lavis’s cinematography concentrates on eerie shadows across faces, the shiny sweat on foreheads and the low florescent lightning that casts a dreary spell over everything. All of it adds quite effectively to the movie’s sense of alienation and despair and John Hawksworth’s alternately brooding and sleazy score is the putrid icing on the rotten cake. Eat it up, yum, yum!

Review by morlockjeff

Movie Morlocks

http://rapidshare.com/files/179625446/SUKEPECOTPH.part1.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/179633280/SUKEPECOTPH.part2.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/179652435/SUKEPECOTPH.part3.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/179652438/SUKEPECOTPH.part4.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/179674023/SUKEPECOTPH.part5.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/179674025/SUKEPECOTPH.part6.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/179686781/SUKEPECOTPH.part7.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/179686782/SUKEPECOTPH.part8.rar

.jpg)

0 comments:

Post a Comment